Hysteria, Valium and Clinical Trials

An in-depth analysis of the under-representation of women in clinical trials and its effects on modern medicine

Background

The aim here is to address and raise awareness of the systemic disadvantages experienced by women within healthcare, partly stemming from the historic disregard of the fundamental biological difference between sexes and the exclusion of women from clinical trials. To preface, a significant proportion of the discussion surrounding changes in legislation and drugs will be in relation to the US, however, similar regulations and findings are followed and observed in the UK and across wider Europe.

Health

Gaps

Individuals can be marginalised by multiple factors, with those identifying with more social factors experiencing more intense discrimination. This also correlates with increased exclusion of their voices and opinions in a society structured to position the white, middle-class, male, heterosexual, cisgendered and able-bodied person in the place of highest privilege. Hence, while this project focuses specifically on the difficulties experienced by women within healthcare, it does not dispute the fact that other groups experience similar disadvantages due to lack of diversity in the medical profession. This includes the elderly, black people, and other ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, those not belonging to the upper classes and the LGBTQ+ community. This marginalisation and discrimination of these groups leads to significant health gaps.

Health gaps are differences in prevalence of disease, health outcomes and access to healthcare across different groups. The Netherlands has the biggest female health gap worldwide, while the UK has the largest female health gap in the G20 and the 12th largest globally- statistics that piqued my interest in this topic. For male health gaps, where women are generally healthier than men, Eastern European countries dominate, with Georgia taking the lead (Men’s health gap, 2020). This seems to stem from societal pressures of traditional masculinity, and as such, men suffer more in countries where levels of gender inequality are high and in those that are traditionally more patriarchal (WHO, 2018). In these societies, ideas of masculinity are linked to health risks that stem from smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse, suggesting male health gaps are culturally/socially induced. In contrast, female health gaps, where men are generally healthier than women, typically arise due to the fact that women are less studied, misdiagnosed and taken less seriously by the healthcare system. This is consistent across a wide range of situations and medical conditions. For example, women wait an average of 65 mins to receive analgesia in US A&Es while men wait only 49 mins, and women are significantly less likely to receive opiates than men, regardless of the doctors’ gender, suggesting an unconscious bias exists within healthcare. (Chen et al., 2008, p416). Similarly, women, in the US, are prescribed less pain medication than men after identical procedures and are instead, more likely to receive sedatives (suggesting women are just anxious or stressed rather than in pain); women are less likely to be admitted to hospital and receive stress tests in a follow up appointment when complaining of chest pain, and women are significantly more likely than men to be undertreated for pain by doctors. (Hoffman et al., 2001, p17). Hoffman et al. also describe a study that found in general, nurses view women as more tolerant of pain, less sensitive to pain and less distressed as a result of pain. However, a literature review found that women may have a lower pain threshold and tolerance than men and that female animals show more pronounced responses to experimental pain. (Barksy et al. p267). Furthermore, the fact women aren’t taken as seriously within medicine is undeniable with respect to heart attacks and heart failure. Women are less commonly diagnosed with heart failure in outpatient settings and have lower rates of primary care follow-up, fewer diagnostic investigations, less treatment initiation, and lower treatment doses than their male equivalents (found in a UK based study). (Conrad et al, 2019, p10). Not only that, but women are also twice as likely to die in the 30 days after a heart attack. This is in part due to the fact that women are at least 13% less likely to receive statins following a heart attack than men of the same age (in a US study) but also because the ‘classic’ symptoms for heart attacks are classic for men. (Peters et al., 2018, p1732). Women are actually more likely to experience breathlessness, fatigue, nausea and what feels like indigestion than pain in the chest and down their left arm. This leaves women apprehensive about seeking medical care when they have these symptoms for fear of being wrong and labelled a hypochondriac. Women’s concerns and suffering are continuously not taken seriously. It is possible to trace these attitudes back to the intertwining of the concepts of femininity and hysteria throughout history and the fact that medicine, and society, since has been built on these beliefs.

“Western healthcare systems don’t ignore women or minimise their suffering because doctors are sexist… Institutions especially those as old and elusive as medicine are inherently conservative because they exist to support the status quo.”

Gabrielle Jackson, (p162-3).

Hysteria originates from the Greek word for uterus (‘hystera’) and relates to the Greeks’ belief that the uterus was free to wander around the body. The illness was also described previously in ancient Egypt. The uterus was considered the root of all illness and marked women as inferior. The definition of hysteria has varied throughout history and has been used to describe women that don’t conform to the expectations set by her society, any ‘female madness’, or more recently, it has been used to describe a psychological disorder characterised by conversion of psychological stress into physical symptoms. Its causes have also varied from the original idea of the wandering womb to a woman’s weaker nervous system, a lack or excess of sex, and to ‘uncontrollable’ hormones. The one consistency here is the blame placed on women: it’s always the woman’s fault. Through the years, hysteria has been treated with smelling salts to encourage the uterus to return to its correct place, vibrators, hypnosis, or, in the Victorian era, a period in an insane asylum. Into the 20th century the treatment plan was generally a ‘rest cure’, where the men in the woman’s life administered bedrest for as long as they deemed necessary. Undoubtedly, if the woman wasn’t already psychologically distressed, this treatment plan exacerbated their suffering. Again, in the 20th century, the advent of Valium in 1963, the sexist marketing that followed and, consequently, its rise to America’s best-selling medicine (until 1982), has been compared to hysteria, with the medication of women, presenting with justifiable concerns, used instead of tackling the larger issues within society causing these reactions. It is important to recognise that the women diagnosed with hysteria throughout history likely had medical issues that would now be recognisable, but yet went untreated. Hysteria was removed as a medical diagnosis from the DSM-III in 1980 but the echoes of hysteria still remain in medicine.

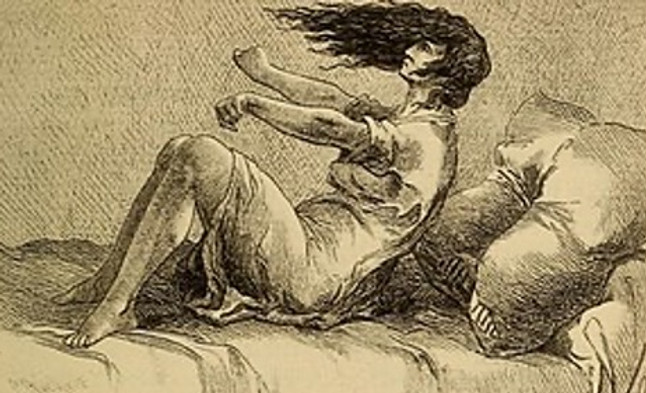

Hysteria

Drawing depicting the movements elicited during a hysterical convulsive attack.

Credit: “Hysteria and certain allied conditions, their nature and treatment, with special reference to the application of the rest cure, massage, electrotherapy, hypnotism, etc” (1897) by G. J. Preston. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hysteria_and_certain_allied_conditions,_their_nature_and_treatment,_with_special_reference_to_the_application_of_the_rest_cure,_massage,_electrotherapy,_hypnotism,_etc_(1897)_(14591998469).jpg]

There is still a tendency within healthcare to attribute the cause of women’s illnesses to their emotional state, with physical issues frequently dismissed as ‘just stress’ or having a too heavy workload, reminiscent of hysteria diagnoses. Many physicians still consider women’s symptoms to be exaggerated or a figment of their imagination. Often, people with undiagnosed neurological complaints are diagnosed with conversion or somatoform disorders, suggesting the symptoms are psychological or psychosomatic if the cause can’t be found. It is worth noting that women are up to 10 times more likely to receive this diagnosis than men (Barsky et al., 2001 p268). The definition of somatoform disorders is painstakingly similar to that of hysteria. Has conversion or somatoform disorders become the new hysteria?

“Hysteria will never disappear because it essentially reinvents itself to reflect the cultures it imitates.”

Gabrielle Jackson’s interpretation of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s (an 18th century philosopher) views on hysteria. (Jackson, 2019, p115).

Gabrielle Jackson, author of ‘Pain and Prejudice’, argues that from her research and interviews with medical professionals, borderline personality disorder, endometriosis, chronic pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome are all considered hysterical conditions, and hysteria has embedded itself into many diagnoses in the DSM, covering other mental disorders, such as bipolar disorder. Commonalities between these illnesses are that they all have a much higher prevalence in female patients, than male patients, and medical understanding of these conditions is limited, with no cure or effective long-term treatment plan. (Jackson, p162). This correlates to how little research funding has been dedicated to learning more about these ‘women’s’ diseases. In fact, in general, most diseases and their accompanying symptoms are studied with respect to the male anatomy, leading to many women being misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed. Similarly, women’s bodies and the health conditions that affect them are less likely to have been studied, leading to many women still suffering due to lack of research into their health. In a form of observer bias, male clinicians are more likely to study men, and considering the history of female clinicians and when women were allowed to become doctors this bias was never balanced out. There is also the trend throughout history of male physicians not examining women; social norms and expectations are harmful to both sexes health’s, as previously suggested by the health gap data. (WHO, 2018).

Pseudo-scientific

Prejudice

In clinical and preclinical research, male lab animals are used more often than female ones, due to the belief that males are less variable than females, again due to female hormone cycles. However, female mice are no more variable than male mice. (Prendergast et al., 2014 p3-4). The sex of cell lines studied in vitro is also too often ignored, despite the fact that female and male cells respond differently to chemical and microbial stressors. (Du et al., 2004, p38565-7). This over-reliance on male animals and cells in preclinical research obscures key sex differences that could guide clinical studies - these important concepts will be returned to in the importance of sex as a biological variable. Fundamentally, the exclusion of women and female specimens from clinical and preclinical research is an act of ignorance rather than a lack of knowledge or access and is traceable to a pseudo-scientific prejudice of women being difficult to study.

“A collection of beliefs or practices mistakenly regarded as being based on scientific method.”

Pseudoscience according to the Oxford Dictionary.

Science is seen as clean-cut knowledge with a right and wrong answer and little room for opinion or varying perspectives, but evidently, this isn’t always the case. It is integral to the health of society as a whole to tackle the issues mentioned and that is the purpose of this site: to raise awareness. It is also worth being aware of problematic language in historical literature, such as ‘were’ or ‘used to’, which reinforce the idea that these issues have been dealt with and that there is an absence of these issues in modern society, as well as perpetuate colonising thinking and behaviour- this is, however, more applicable to other groups that are marginalised within medicine. Nevertheless, what is important to remember is that women can still be (and still are) under-represented in clinical trials, and even when they’re not, the lack of sex specific analysis leads to women experiencing almost twice as many adverse drug reactions compared to men. (Zucker and Prendergast, 2020, p11). Accordingly, the rest of this site is going to cover the history of clinical research, including the inclusion, or rather the exclusion, of women, and the importance of sex as a biological variable in clinical trials, with reference to Valium.